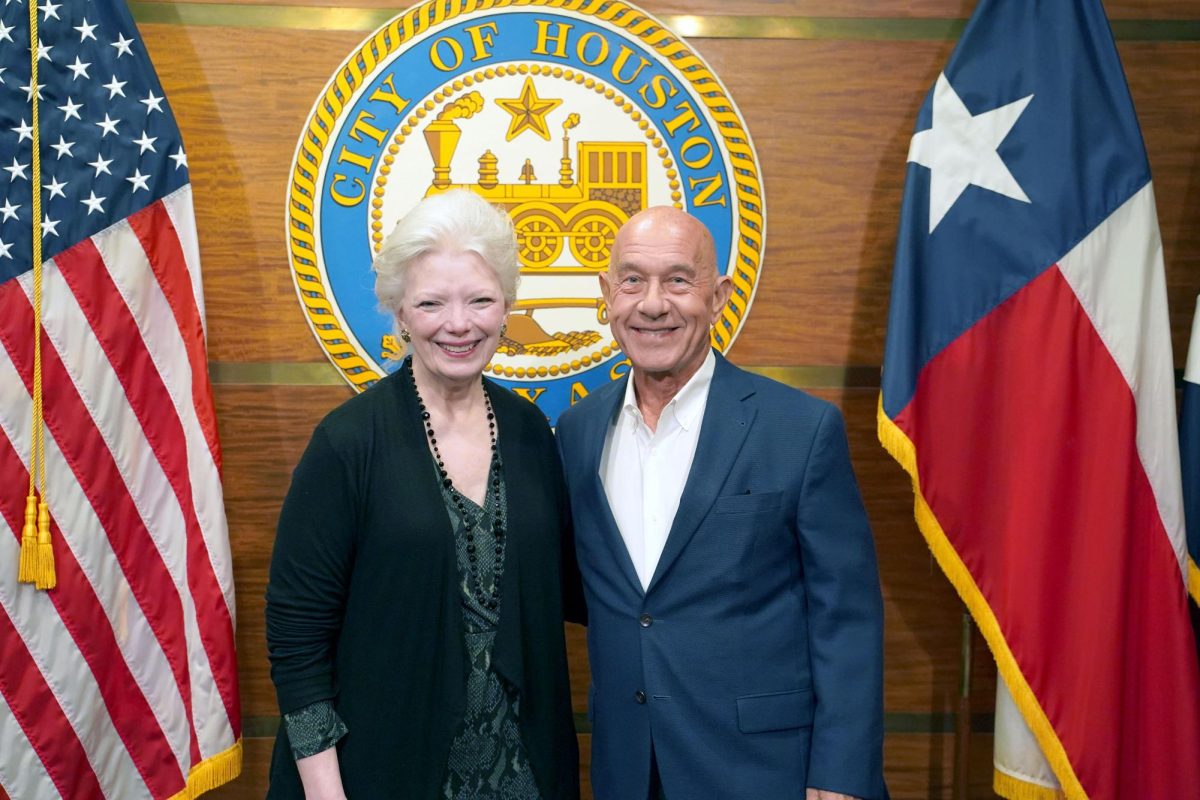

HOUSTON – Mayor John Whitmire understands that Kingwood residents are frustrated and worried. Hurricane season begins on June 1, and many families in the “Livable Forest” are still recovering from last July’s Hurricane Beryl.

During the Beryl recovery, families spent more than a week without power in an intense heatwave. Powerlines laid dangerously across hundreds of backyards. And debris lined the streets of Kingwood well into August.

“Kingwood has a legitimate complaint and concern,” Whitmire said.

That is one reason he is working hard with Kingwood’s city council representatives as well as local first responders to strengthen the relationship between the Houston mayor’s office and Kingwood.

“I think every community that is hit repeatedly starts to feel a little torn by Mother Nature,” said Angela Blanchard, Houston’s Chief Recovery and Resilience Officer. “But the truth is, if you look across the world, these incidences, especially for a coastal city like this one, have increased in frequency and severity.”

Kingwood is full of vulnerabilities during storms. It is situated near the West and East forks of the San Jacinto River. It also sits 80 miles away from the Gulf of Mexico. In addition, the community is filled with trees. Kingwood bills itself as “The Livable Forest.”

Being a part of a coastal city, Kingwood is prone to more rain. With the San Jacinto River surrounding most of the suburb, it is susceptible to flooding.

The problems with flooding and storm damage in Kingwood made national headlines for the first time when Hurricane Harvey hit in 2017.

In August 2017, the Category 4 hurricane brought more than 20 inches of water toward Lake Conroe. In response, the San Jacinto River Authority did an emergency release of water from the Lake Conroe Dam.

That release caused Lake Houston to rapidly overflow its banks, flooding Kingwood days after the hurricane hit the area. As a result around 5,000 homes, numerous businesses and even Kingwood High School flooded.

Harvey was referred to as a “100-year flood.” But two years later, the community was reeling again.

In May 2019, a storm caused severe flooding after the community received 10 inches of rain. About 400 homes were flooded, and students were stranded at school for hours. Two students even spent the night at Kingwood Park. More students spent the night at Kingwood Middle School and Elm Grove Elementary. It ended up being called “the May floods.”

Just four months later, Kingwood was hit again on Sept. 19.

Junior Elena Amos was in sixth grade when she huddled on the dining room table with her dad and little sister as water rose in their home.

Tropical Storm Imelda dropped 30 inches of rain, becoming the fourth wettest tropical cyclone to impact Texas.

“It was so scary my dad had to go turn off the electricity so it wouldn’t catch on fire,” said Amos, whose home also flooded four months earlier in May. “My sister was just holding on to me so tight. She wouldn’t let go.”

Amos lives in Harris County, but near the Montgomery County border. Her dad called the police four times asking for help to escape. No one showed up.

After four hours of huddling with his daughters on the tabletop, Amos’s dad spotted a police boat motoring by. He caught their attention. Even though they said they had not received any of his calls, they took the family to safety.

The day traumatized Amos and her little sister.

“For a while, anytime they said there might be a hurricane coming, we would just put our stuff up high and go to my grandparents’ house,” Amos said. “Anytime my sister would see rain at her preschool or thunder, she would freak out. She would start crying.”

Just last May, a derecho storm hit the Houston area, leaving around a million Houstonians without power. Kingwood Park had power and held school, but its feeder schools lost power and had to cancel classes. Most Kingwood Park families were without power for more than 36 hours.

One big concern after the derecho was the fact that hurricane season had not even started yet. The concern ended up being valid.

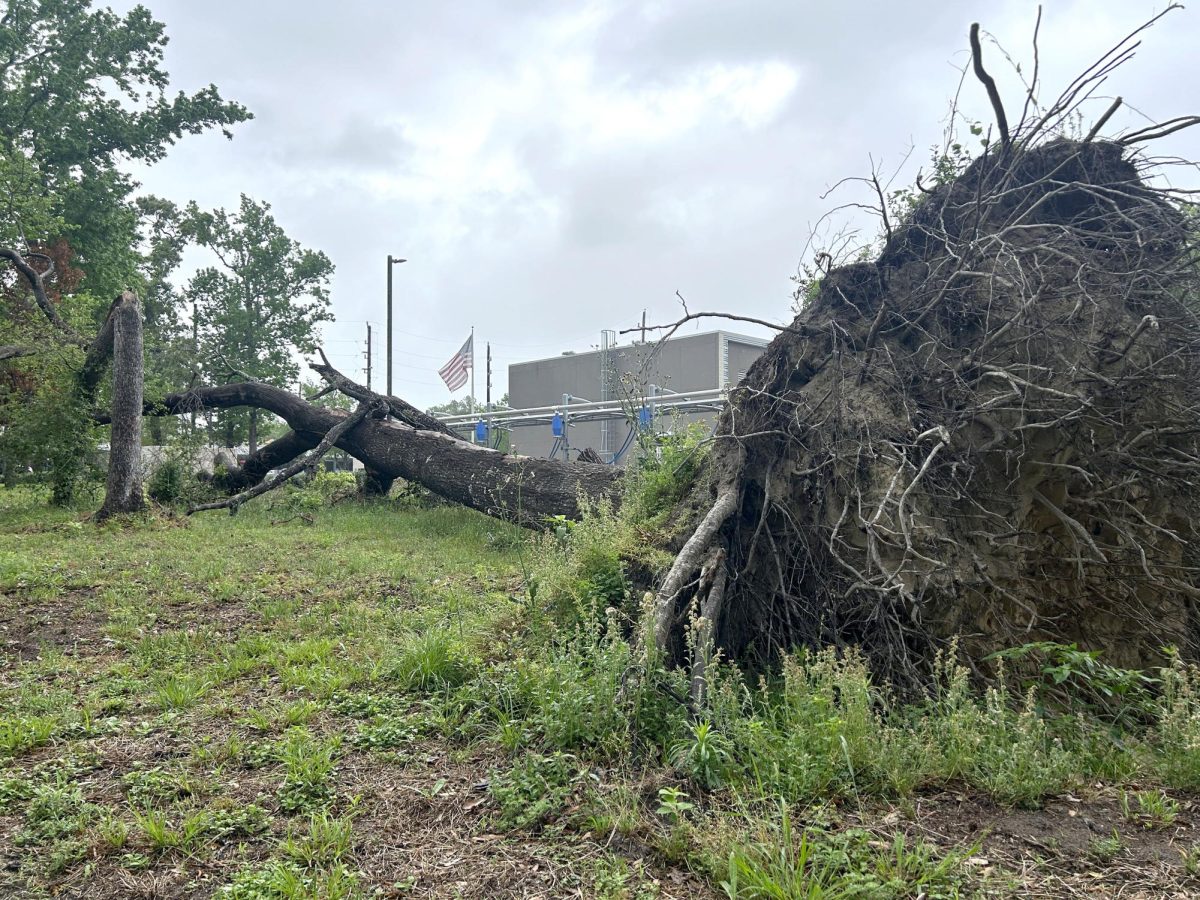

On July 8, Kingwood residents woke up to the damage of Category 1 Hurricane Beryl. The hurricane brought winds of 80 mph, and it is estimated that the winds impacted about 50% of urbananzied-area trees. Trees were snapped in half or were completely uprooted in almost every corner of Kingwood.

The storm left around three million people in the Greater Houston area without power. Most neighborhoods zoned to Kingwood Park were left powerless for more than a week. In many neighborhoods, like Woodland Hills, homes had to be completely rebuilt. Some still have not returned home.

Chemistry teacher Laurie Rosato has experienced her share of hurricanes. She survived Hurricane Andrew in Miami, Hurricane Katrina in Louisiana and Hurricane Harvey in Kingwood.

Through it all, she has learned what she can handle and what she can’t. She left Kingwood right after she lost power during Beryl.

“I never think, ‘Oh my God, I might lose my house,’” Rosato said. “I mean, I sometimes kind of think that, and I’ve done things like try to lift my furniture or my stuff to protect it. But I’m just such a princess that the thought of no power makes me like, ooh. That’s why I want to evacuate. It’s because of power.”

In Louisiana, Florida and in Texas, Rosato has seen so many families lose everything. And she hopes the government makes tangible changes soon.

“We’ve got to get the infrastructure that needs to be in place so that more flooding doesn’t occur – to control the flooding, to control the power grid,” Rosato said. “And support, there needs to be governmental support for people who lose their homes. Because if you don’t have insurance or even if you do have insurance, and then they cut you off, you need to be able to recover from that.”

The challenges faced in Kingwood and throughout Houston during Beryl led to Whitmire’s latest goal.

The city is working toward having generators at critical places in communities like police and fire stations, multi-service centers, libraries, water pump stations, sewer plants and animal shelters.

“We have a real ambitious goal to try to find 100 city service centers for generators,” Whitmire said. “We are well on our way. Everybody has to have access to generators. We’ve got to be able to provide cooling spaces, heating spaces and certainly refuge.”

This administration has made it a priority for every Houstonian to be able to call emergency services, turn on water and get to places of refuge during disasters.

Other than providing generators around the city, the mayor’s office continues to work with councilmen, state officials and federal officials to prepare for any disasters that may hit Houston soon.

“There are some resources that are always going to have to come in from the outside, and expediting that requires good relationships and trust,” Blanchard said.

Before becoming mayor, Whitmire spent 50 years in the legislature.

“State officials trust our mayor,” Blanchard said. “That has meant millions more dollars to recovery than we’ve gotten, and his work with TDEM (Texas Department of Emergency Management) and the governor’s office has meant an expedited funding.”

As much as the administration wishes to prevent every Houstonian from being impacted by any disaster, it is just not plausible.

Blanchard said she believes that everyone should have an emergency plan at their home, in their car, and people need to be aware of the plans at their schools and places of work.

She emphasizes all families need to be “360 degrees prepared for 365 days,” meaning be ready for anything at any time.

As hurricane season nears, the mayor advises Houstonians to stay vigilant and listen to the city and first responders as disasters arrive.

“I don’t shout wolf. I don’t play scare tactics. I don’t have unnecessary press conferences,” Whitmire said. “We’re direct, we’re factual, we’re compassionate, and experience matters. I would urge people to listen to the authorities.”